Finding we are not alone. (Lk. 24.13-19, 28-31)

Jeremy Rutledge, Circular Congregational Church

April 14, 2024

It hadn’t really been that radical an idea, but it got him kicked out of the Methodist church. And it hadn’t even been his idea. John Murray heard it first from another preacher in London in the 1750s. Universal grace, it was called. The idea that Love wouldn’t ultimately condemn anybody, but all would find forgiveness, acceptance, and belonging.

John Murray had been raised in a strict Calvinist homewhere he was taught from an early age the idea of chosen-ness. He thought that was inconsistent with Love and developed a theology that he believed was much better. He had heard universal grace preached, and, given his background, he interpreted it in a way that dismantled the idea of chosen-ness. If Love took everybody in, then everybody was chosen. Or perhaps nobody was. In any case, the point was that nobody was better, or more chosen, than anybody else. We were all equal in Love’s eyes. Every person beautiful and beloved. No person condemned.

John Murray believed that wholeheartedly, preached it, and was kicked out of the church for it. He swore he’d never preach again afterwards. Years later, after suffering the deaths of his wife and son and serving time in debtor’s prison, Murray set sail for America where he hoped to live out the rest of his days unremarkably. Little did he know what was in store. The ship he sailed on struck a New Jersey sandbar and the passengers went ashore at the farm of a man named Thomas Potter.

Thomas Potter was deeply religious, but he hadn’t liked what he had heard in churches; it was too judgy for him, it created insiders and outsiders, it failed to understand the heart of good religion. Potter had built a small chapel on his farm where he had visiting preachers speak, but he hadn’t cared much for any of them, either. That is, until John Murray arrived. When Murray’s background was revealed, he was invited to preach. He was initially reluctant, but he could not resist the kind farmer’s invitation. Imagine how he must have felt getting up to preach when he had been previously shunned for what he said in England. True to form, John Murray preached a sermon on universal grace. To his surprise, Thomas Potter loved it. It was just what he’d been waiting to hear.

There’s a lot more to the story, as Murray’s sermon at Potter’s farm is cited as the introduction of universalism in this country. John Murray traveled up and down the East Coast preaching, in his words, “not hell but hope,” a message that proved quite popular at the time. Later, Murray and others founded the first Universalist Church in Gloucester, Massachusetts. It’s still there, preaching messages of hope to this day. Yet for our purposes this morning we might just consider Murray’s core convictions: Nobody is condemned. All are loved. And nobody is more chosen than anybody else. All are equal in dignity and value.

Think of these commitments in light of the current news: People who want to take our country back and privilege only a few. Groups who claim they are the chosen people of a place; they and no one else. Politicians who take rights away from some while retaining those same rights for others. All these strata of value, all this judgment and condemnation in the air around us. Some days we may long to set our newspapers down and simply read one of John Murray’s old sermons instead. Some days we might wish that our world would just get with it at least as much as they did in 18th-century New Jersey.

I was remembering that old story this month as I read an extraordinary article in The Atlantic. The article, entitled “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust,” was written by an agnostic named Derek Thompson, who found himself surprisingly concerned that religious participation in America is in steep decline. “More than one-quarter of Americans now identify as atheists, agnostics, or religiously ‘unaffiliated,'” Thompson wrote. They have good reasons for it. Religious institutions can feel insular, arcane, and out of touch. The scandals of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church and other churches has eroded trust in religion and associated it with great harm. And the politicization of evangelical Christianity, beginning decades ago with groups like the Moral Majority and extending to today’s evangelical embrace of deeply intolerant, right-wing politicians, have simply put many people off religion altogether. It is increasingly common for people to live their lives without any religious connections. As Thompson noted, “More Americans today have ‘converted’ out of religion than have converted to all forms of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam combined. No faith’s evangelism has been as successful in this century as skepticism.”

It wouldn’t seem that such a trend would bother an agnostic like Derek Thompson, but he explained that it had caused him to worry about something he hadn’t considered before. Religious institutions, he said, when they were healthy, were places of deep and meaningful human connection. And as we live more and more of our lives online, as we struggle with an epidemic of loneliness, as we feel more fragmented, frustrated, and polarized, we need places to connect. Thompson worried that what was being lost was not really being replaced. Maybe it wouldn’t be a bad idea to connect with a healthy religious community, wondered the agnostic author.

Perhaps what’s so interesting about Thompson’s article is that you can almost hear him wishing for communities where skeptics, seekers, agnostics, doubters, and dissenters might feel more at home. So many have been forced from religion by their questions or by its harms. Others have been kicked out like John Murray for his conscientious convictions. Still others haven’t ever really felt welcome to be their true, authentic selves in religious spaces. But what if there were more churches, for example, that added to their welcome the welcome of freethinkers and free spirits? What if there were more of us who, like Thomas Potter, just made our own space, opened it to all, and waited to see who would come with a fresh word? On a good day in this church, I think we actually do practice this kind of inclusivity. Yet I still wish we had a few more skeptics, agnostics, and doubters. The beloved community, as I understand it, takes all kinds. And is far better for it.

It brings us, for a moment, to our morning scripture lesson. In it, we are told of two people who are walking from Jerusalem to Emmaus. They are talking about Jesus, who then appears to walk alongside them, but they do not recognize him at first. And since I want to be inclusive of freethinkers, please know that our liberal interpretation of the story is that its truths are poetic and not literal. The idea is that Jesus, who represents the holy, the sacred, or the divine in the story is right there with the people, and they do not know. So they tell Jesus the story of what happened, befriend him, and at the end they invite him to share a meal with them. As the story goes, it is only when they gather around the table and Jesus blesses the bread that they realize it’s him. And then he vanishes.

I loved this story when I was a boy because I could sense its inherent playfulness. It is gently reminding us all that the sacred is close at hand and we do not recognize it. Our work then, or a part of our work, is to pay closer attention. To the stranger. The new friend. The conversation we are having. The meal we are sharing. The most ordinary human moments in our day. Each of them connecting us deeply to each other if we are so attuned. I loved how the characters in the story found they weren’t really alone. The characters on the road to Emmaus. The characters at Thomas Potter’s farm. Maybe even the characters at Circular Church or those walking in off the sidewalk to join us.

And here’s where I think the church can get at the heart of what is hurting in us. Derek Thompson cited the work of social psychologist Jonathan Haidt. According to Haidt, as we are increasingly subsumed by the internet, the virtual world, our lives slowly become more disembodied, asynchronous, shallow, and solitary. Yet religious communities and rituals, when they are truly healthy, can provide a counterbalance to the trend. When we engage in real community based in conscience, conviction, and service to others, our lives may begin to feel more embodied, synchronous, deep, and collective. This is why an agnostic found himself writing an article lamenting the decline in religious participation. We need each other, he was saying. We need to find each other and know that we are not alone.

I sometimes read articles like this and wonder for a moment about the future of the church. Will it last? Will it be helpful? Will it matter? But I am reluctant to draw any conclusions. After all, John Murray was once convinced the church wasn’t worth much and he would never preach again. What seems more important than speculation is simply giving ourselves to the work of making a space for everybody, here and now. And constantly trying to expand that space to include more and more people. You know, because nobody is more chosen than anybody else. All of us are equal in dignity and value. And Love means to invite everybody in.

Amen.

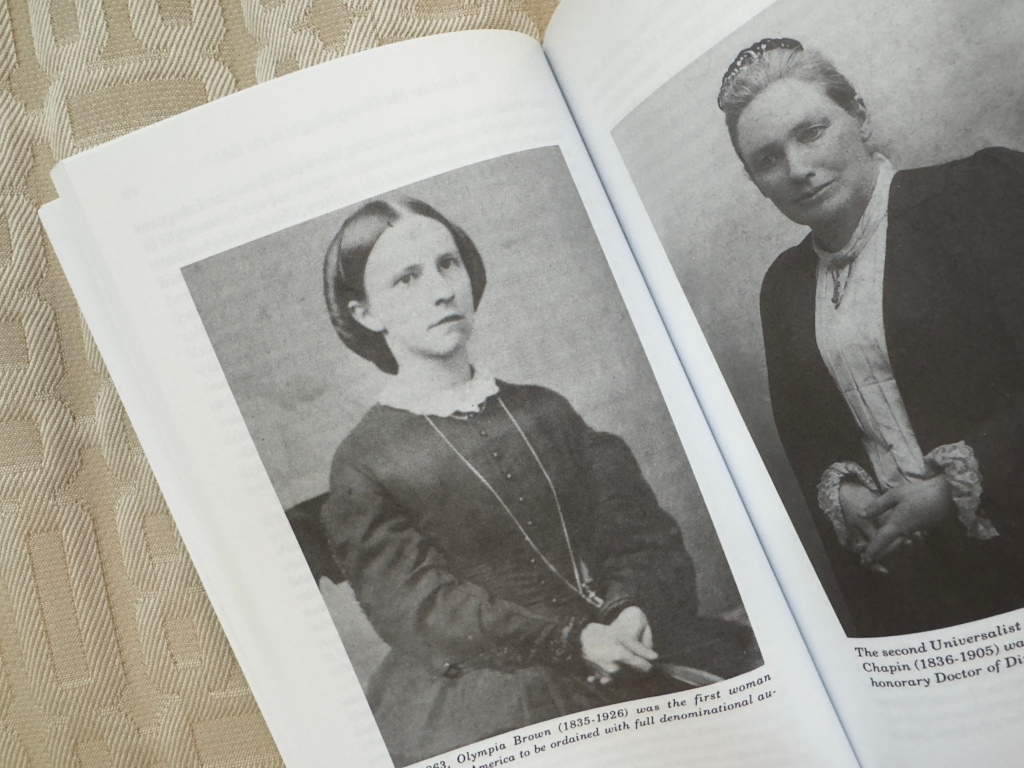

See Charles Howe, The Larger Faith: A History of American Universalism (Boston: Skinner House Books, 1993)

Derek Thompson, “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust,” The Atlantic, April 3, 2024, accessed online at https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/04/america-religion-decline-non-affiliated/677951/

Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness (New York: Penguin Press, 2024)

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article